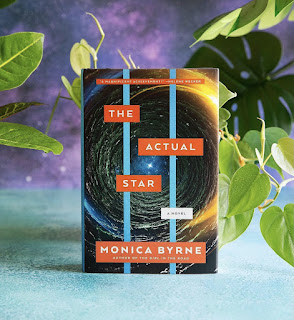

I interviewed Monica Byrne about writing The Actual Star, an epic tale of self-discovery that spans millennia and questions the very meaning of civilization. Born of extensive research into Maya history and culture, this wildly ambitious speculative adventure will challenge you to reframe the past, present, and future.

Monica is also the author of The Girl in the Road, as well as a prolific playwright and screenwriter—an artistic career supported by her patrons on Patreon. In the following conversation, we discuss her creative process, what she learned writing The Actual Star, some of the big ideas the story explores, and the power of speculative fiction.

|

| Photo credit: Tiffany Anderson. |

What is The Actual Star’s origin story? How did it grow from the first glimmer of an idea into the book I’m holding in my hands right now?

I visited Belize in 2012 to see the places my mother had taught in 1963 as a Papal Volunteer. I signed up for a day trip to the sacred cave Actun Tunichil Muknal, which… changed everything.

If you’ve read the chapter of Leah’s first excursion into the cave, that was pretty much my experience. I felt all that euphoria. I came out and my first thought was “I have to go back,” and my second thought was “I have to write a play about this!” I was revising my play What Every Girl Should Know just then, so I had playwriting on the brain. I called the new play The Cake or the Onion. I wanted to write something happening on three different levels of a stage, in three different time periods, that intersected like a symphony. But the more I thought about it, the less a play seemed to “fit” the enormity of the ideas that were coming up, and so I switched to it being a novel instead.

What surprised you most in your research on Maya history and culture? What are the most important ways in which many of us misunderstand the Maya? How did Maya thought influence how you approached telling this story?

What surprised me most was appreciating the logic of human sacrifice. It’s a universal technology, not all that different from what we do today; it’s just that today, the altar is capitalism, and the human bodies are on the other side of the world. At least the ancient Maya were upfront about it.

The most common misconception in the U.S., at least, is that the ancient Maya “disappeared.” They didn’t disappear at all—only some elite state apparatuses of the Maya fell, because they no longer served Maya people. Maya communities re-formed and thrived, and continue to, to this day. But the persistence of the “disappearance” story serves a convenient, racist narrative, that the American continents were somehow empty when Spanish invaders arrived; or even if there were people here, they were ignorable. That narrative has daily, disastrous consequences for modern Maya communities all over Central America, as in the Guatemalan genocide of the early 80s.

How did depicting past, present, and future civilizations change your personal definitions of “civilization” and “progress”?

What most folks see as “civilization” in the archaeological sense is actually a very narrow definition of it: those which leave behind stone monuments and/or written records. If you define “civilization” as a group of people living together, which I do, the vast majority of civilizations didn’t do this. Does that make them any less civilizations? No—but it does make them less knowable via the Western toolbox and Western criteria we prioritize, which is frustrating. But what if we put far more emphasis on, for example, tracing oral histories than digging up stone? There are so many ways to illuminate the past that don’t necessarily get equal funding or attention.

And yeah, progress is a myth. The ancient Maya knew that! They saw time as cyclical, not linear. They built collapse into their understanding of the universe, whereas we still labor under the delusion that time is a straight march into laser guns and starships.

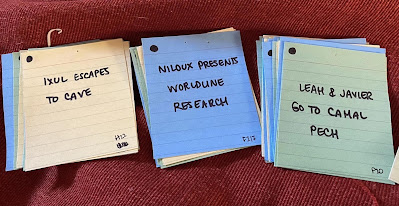

What creative challenges did you encounter weaving so many disparate threads into a single story? How did you overcome them?

I can just say that it was very, very difficult; and that I used many, many colored index cards.

|

| Photo credit: Monica Byrne. |

What did writing The Actual Star teach you about craft? What advice can you offer other writers looking to develop and grow?

I would say to pay attention to whatever gives you butterflies in your stomach. This book took eight years—not just the research journey, but the publishing journey. It was a nightmare. It still is, in some ways. But do I regret writing and publishing the book? Not for a second. Because that feeling I got in the cave, that gave me butterflies in my stomach, is real and pure and good, and I’m honored to be its vessel. So my advice to writers is: find whatever is trying to find its expression in you, and become its loving servant.

What did writing The Actual Star teach you about life? How are you different for having written it?

That it’s okay if things fall apart. That that, in fact, is the nature of the universe.

What does speculative fiction mean to you? What role does imaginative literature play in the culture?

It’s a prism. Imaginative fiction—mythic, speculative, genre, fantastical, or science fiction, whatever you want to call it—is the prism through which we aim the white light of our current “reality” and see the full array of colorful possibilities projected on the wall, that are all contained within the original light. For me, this is a far, far more exciting endeavor than just writing the white light itself.

How has your relationship with your readers shifted since starting your Patreon? How is the feedback loop between authors and audience evolving, and how does that impact book publishing?

My patrons and my readers are my rock. They really are. They support me both financially and emotionally, especially when the publishing industry does not. Like all relationships, it takes work, but I base mine on transparency, accountability, care, and joy; and it’s worked out really well so far. I just wish all writers were able to be directly supported like this—because for the most part, the publishing industry sets up all but the most wildly privileged writers to fail.

In the acknowledgements, you mention that Kim Stanley Robinson is a foundational writer for you. What do you love about Stan’s work, what have you learned from it, and how did it influence The Actual Star?

Oh, where to begin! I read Red Mars when I was sixteen, and have been reading him ever since. The most important thing is: I felt he treated science fiction as being as real as everyday life. I was raised on Star Wars, so I needed to see that science fiction could also be this—that technology wasn’t just shiny metal parts, it was also the intimate work of human bodies. There’s a LOT of Stan’s influence in The Actual Star. Some of it is explicit and borrowed (for which I asked permission)—like the naming convention for reincarnated characters, and the concept of documented anarchy. But then there’s just the messiness of human self-governance. I thought of the Mars trilogy symposiums when writing the tzoyna scene in Teakettle—just, around and around and around, and feeling like you’re getting nowhere. We think everything will be sterile and efficient in the future? That’s a masculine fantasy. It won’t be.

What books have changed your life? What should fans of The Actual Star read next?

Go read Pleasure Activism by adrienne marie brown. Her writing and organizing are acts of science fiction, because she’s imagining new paths into the future—even if her books are not shelved as such. And she (along with Walidah Imarisha) are the ones who taught me that.

*

Complement with Kim Stanley Robinson’s lunar revolution, Annalee Newitz on who owns the future, and the best books I read in 2021.